Every agricultural society is also the story of textiles.

Where people stopped long enough to live and grow food, there is archaeological record of flax or early cotton varieties also being grown.

Households intercropped edible plants with plants that could be woven, and every home in all probability had a loom of some kind that cloth could be woven on. Backstrap looms for nomadic people, pit looms for those more settled, the wooden evidence is often lost in the past but the fragments of fabric found through the archeological and cultural records indicate looms in domestic settings for millennia.

Weaving was an everyday household activity pre-industrialisation.

Often in the women’s domain, as spinning, laying the warp and weaving were less dangerous than hunting, and working the land. Women could have a babe in a cot by the spindle, or keep an eye on toddlers as they grew. Children would learn on a toy loom. Older women had skills they passed on generationally. In some cultures, the loom became part of the myth. Greek myths talk of weaving songs that Cerces sang, readily identifying her activity in a way listeners to the stories of the Greek Gods would know.

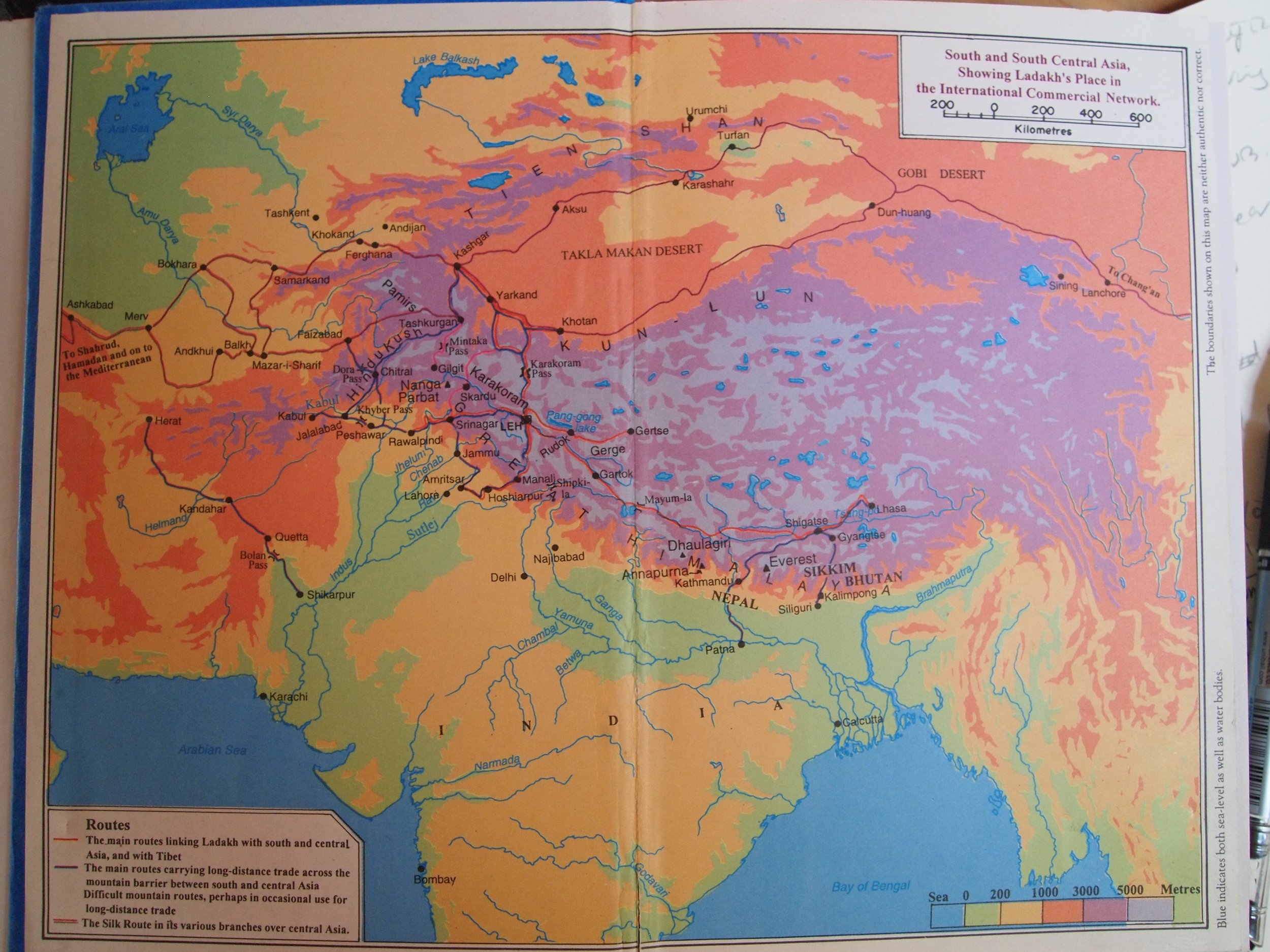

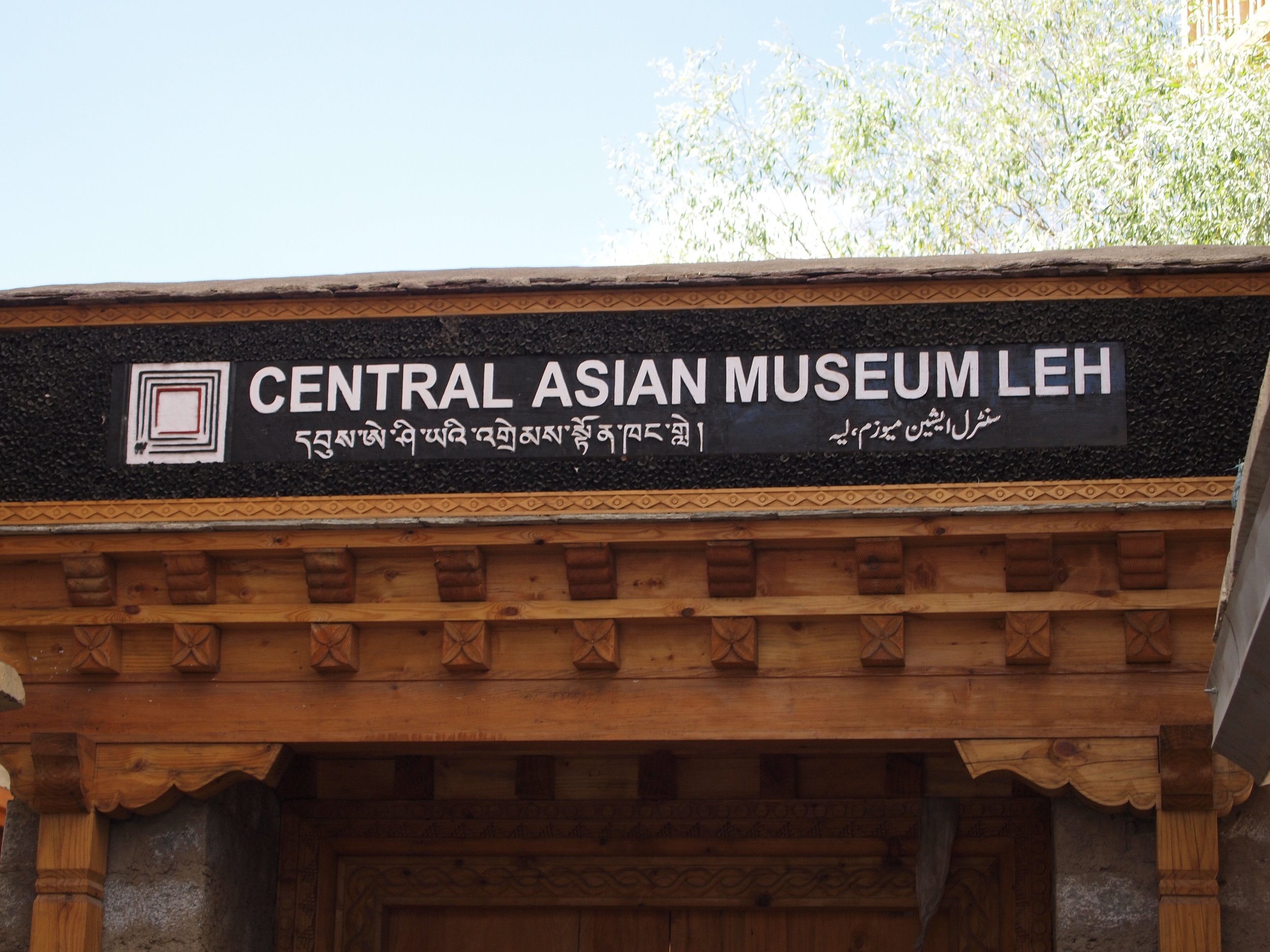

Weavers in the high Himalayas of Ladakh, India, talk about the unending yarn representing their progeny, the weft the mother, the warp the father. They are weaving their family each time they create a shawl or a blanket, reiterating their family tree.

Creating their place in the world and weaving an identity.

The fundamental role of garments is to wrap the human body to protect it from the elements, keeping us protected from the environment. From baby blankets to shrouds, textiles are with us from the moment we are born to the moment we die. We have imbued cloth with religious, cultural, social and economic significance from society to society and culture to culture. The raw materials and styles may shift but the fundamental service a garment provides remains the same. Along the way cloth has found a niche in our households, replacing animal skins as soft furnishings for our modern caves. Linen sheets, chintz curtains.

Despite the Industrial Revolution changing the textile industry forever, the need to weave traditional designs on wooden looms has remained strong in India. As I’ve worked my way north and south, east and west, I am struck by how I almost always see a loom in rural villages.

Some of the raw materials may have changed but the designs continue, and the recognition that these are skills passed generationally.

“My father taught me”. “My grandmother shows me” . How often have I heard references to spinning and weaving that include family. These skills are recognised as inter-generational wealth.

I worry that the short attention spans created by our damaging social media will be the final unlocking of an activity that stretches back to our first knitting of strings and the need for a bag to carry food in.

I sincerely hope that taking small groups of interested people to see how handlooming works will be part of the influence on the next generation to weave economically, where responsible, respectful tourism has a force for economic good.

Losing our Ladakhi pashmina goat herders to the forces of Netflix might be something later regretted.

The language of life is woven through with terms that belong to textiles. In English we idiomatically use terms such as frayed or warped, I’ve lost the thread, blanketed with love, life’s rich tapestry. Without always recognising these are terms from our textile past. We can really say that textiles are woven into our past.

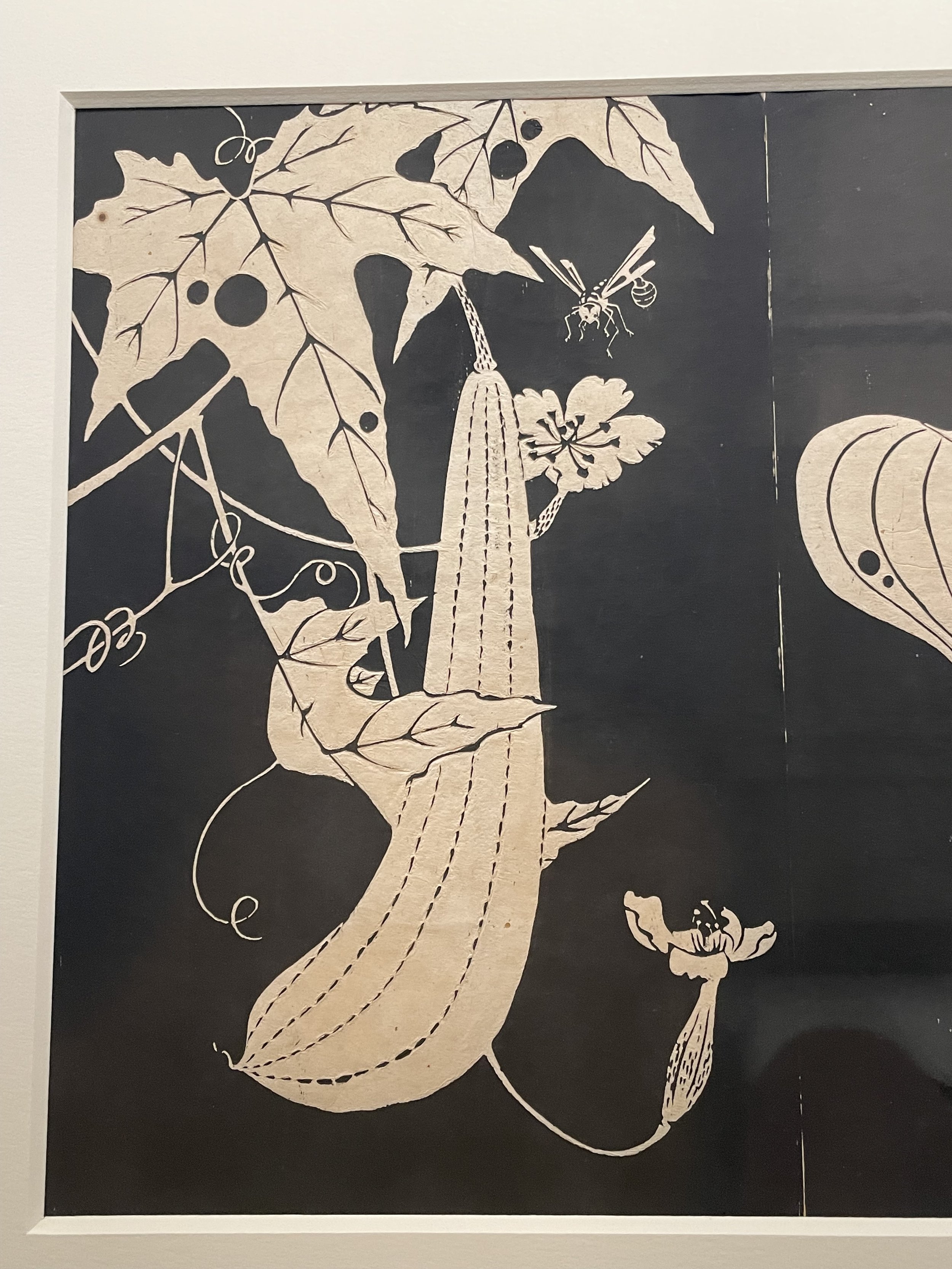

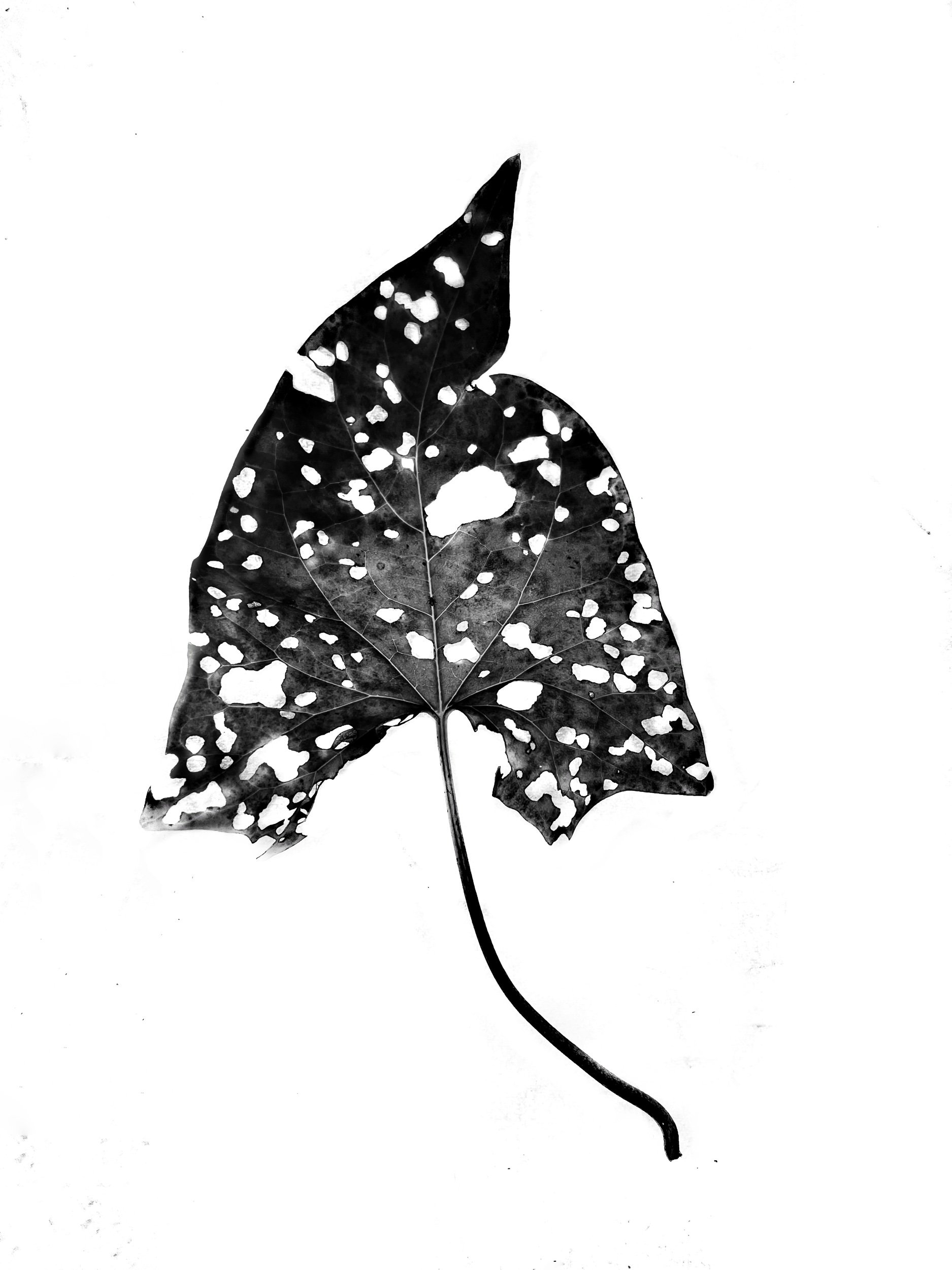

Not every region has the climate or soil to grow flax or cotton. Colder mountainous regions made use of animal wools to keep them warm. The biome provides the soil and the rainfall, the habitat for the beetles used to dye cloth and for the plants such as madder or indigo for reds and blues. Lichens, shells, insects, berries, leaves and bark all provide a natural biodiversity that humans explored for colour.

It’s my thinking that the more arid the environment, the brighter the weaving colours. Temperate climates often produce soft tones - think the heathers and greens of Harris Tweed. Gujurat, on the other hand, and Rajasthan, are more arid regions and the colours lean towards hot pinks and bright yellows. Now the product of modern dyes, these were once dyed from the local vegetation, but I often wonder if the dryer the climate the bigger the need for strong colours to offset the dry and the dusty. A cultural response to the characters of a biome. And the brighter light reflecting off the desert mica, intensifying the hues.

I’ve been reading about the history of the cotton industry and the shift from household to mono crop. Post industrialisation, I had not appreciated the extent to which cotton for the textiles industry shaped policy decisions on economic and political matters. I certainly had not read about the crisis India’s hand loom weavers found themselves in as the mills of Lancashire rose and how the hand weavers of India were forced into unemployment and starvation by appallingly low wages to reduce competition.

Visiting regions in India where handlooming is functioning economically feels to me like the closing of the circle. The Lancashire mills, long since defunct, have not stayed the pace. China’s capacity for production has allowed it to dominate the power loom textiles export market, with India close behind. The natural pace of handloom will always keep it small scale.

Strength comes from creating hubs and cooperatives, and allowing the artisans to shift with the market forces in terms of design.

Buyers from elsewhere need to be reminded that handmade is dependent on weather, the supply lines of raw material, and that new designs are interesting but take time to develop and iterate on the loom. Weavers need their own projects to keep them interested and growing creatively. Handmade cannot replicate the speed and volumes of machine made.

I’m very interested in the resurgence in old world cotton, and the ways in which old indigenous species are making a come-back. I’m hoping to see these growing for myself and talk to the farmers working with old drought-resistant strains.

In November 2024 I’m leading a textiles tour in Gujurat. This is a wonderful opportunity to meet the artisans directly and explore skills and techniques through workshops and demonstrations. Do join me in supporting the artisans directly.