The images and writing here give an insight into my practice, my creative interests and the fuel that feeds them.

My work tends to fall into three main categories: landscapes, studio work and portraiture. There is often a seasonal element to this. Commissioned location portraits tend to happen around the warmer summer months, and the landscapes and seascapes are more often taken in spring and autumn when the weather is changeable. Studio work happens in late autumn/winter for more reflective, quiet creativity. The Indian trips are (in normal times) either side of December.

Landscapes and Seascapes

A lot of my landscape work references marine and freshwater environments. I live on an estuary, where stormy seascapes and turbulent clouds draw me in, and I seek out those moments where changing seasons cause colliding fronts and atmospheric upheaval.

Lighthouse, Burnham Sands © 2020

Insectarium

The Insectarium began life as a childhood obsession with bugs, beetles and insects. As an adult, I notice fewer moths circling my bedroom light at night. This series brings focus to insect habitats at risk and the impact of light pollution on insect behaviour. Moths are critical pollinators, often overlooked, and their range of scale and beauty is extraordinary. These are insect portraits taken in the studio, using humane catch and release techniques, and the plan is to hand-print these using photogravure techniques bringing depth and luminosity to the prints. A research residency in Japan to Okinawa and the mainland will bring moth-hunting opportunities, and the series is planned to expand to include these findings.

Vintage Yashica on Tripod, Burnham Sands © Nov 2020

Tools of the Trade:

Vintage analogue cameras (medium format) and full-frame Digital SLRs, and my iPhone. The images are inspired by the timeless quality of early black and white images taken on medium and large format cameras.

Crepuscular Light Rays, Bosham Creek © 2020

Jutland Dunes, © 2020

Studio work, papers and print-making

The arrival of the studio in my life has given me creative space, physically and spiritually. Recent land and seascapes I’ve been working on from 2020 were taken in Somerset, Chichester Harbour, mid-Wales, Cornwall and Northern Denmark, all sharing big skies, stormy weather and amazing light.

Printing

Some of the commissioned portraits and seascapes were printed on bamboo papers as part of a general move towards sustainability, and this has found its way into thinking about alternative chemical processes. My current printing process is giclee printing on archival paper (mainly by Hahnemule).

Papers and print-making

I am drawn to the use of intaglio techniques and handmade papers, of which I have a large collection waiting for the right print. The polymer photogravure seems a perfect combination of old and new techniques: carefully etched plates, mixing-up inks and print-making with a traditional press and felt blankets.

These photographic etching techniques, bring into play the possibilities for double exposures and the rolling negatives of the analogue cameras, and the use of beautiful, hand-made papers carefully wetted. My old vintage cameras have a touch and feel that I find familiar, and I’m open to the gifts of chance as opportunities for creativity.

Taking etched photographs and using intaglio printing techniques to print these breathes life into papers. Water is fundamental to making paper, and fundamental to the intaglio technique. I have watery tendrils connecting my work in theme and physicality. My work is becoming more artisan, more ink-stained, part of a larger print-making, photographic community.

Mountain Ash near Standing Stones, Mid-Wales © Oct 2020

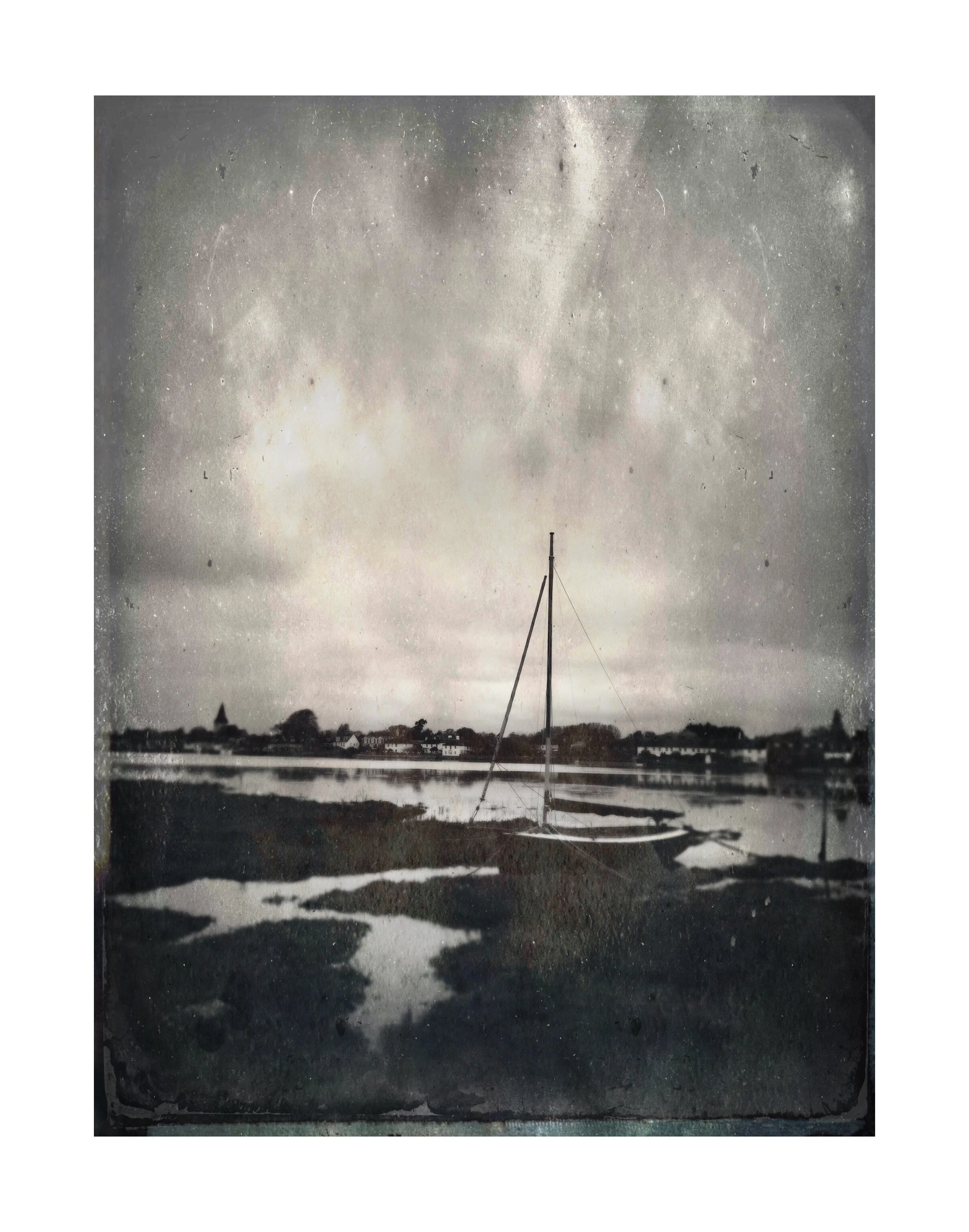

This print below is of one of my favourite wooden boats in Bosham Creek, speckled with dust from a dirty negative. I remain fascinated with TinType. The use of negatives to create positive images has seemed like an alchemy, and when negatives are altered or damaged, there is an added layer of visual language both unexpected and attractive. The dust and scratches hold their own story.

Bosham Creek © 2019

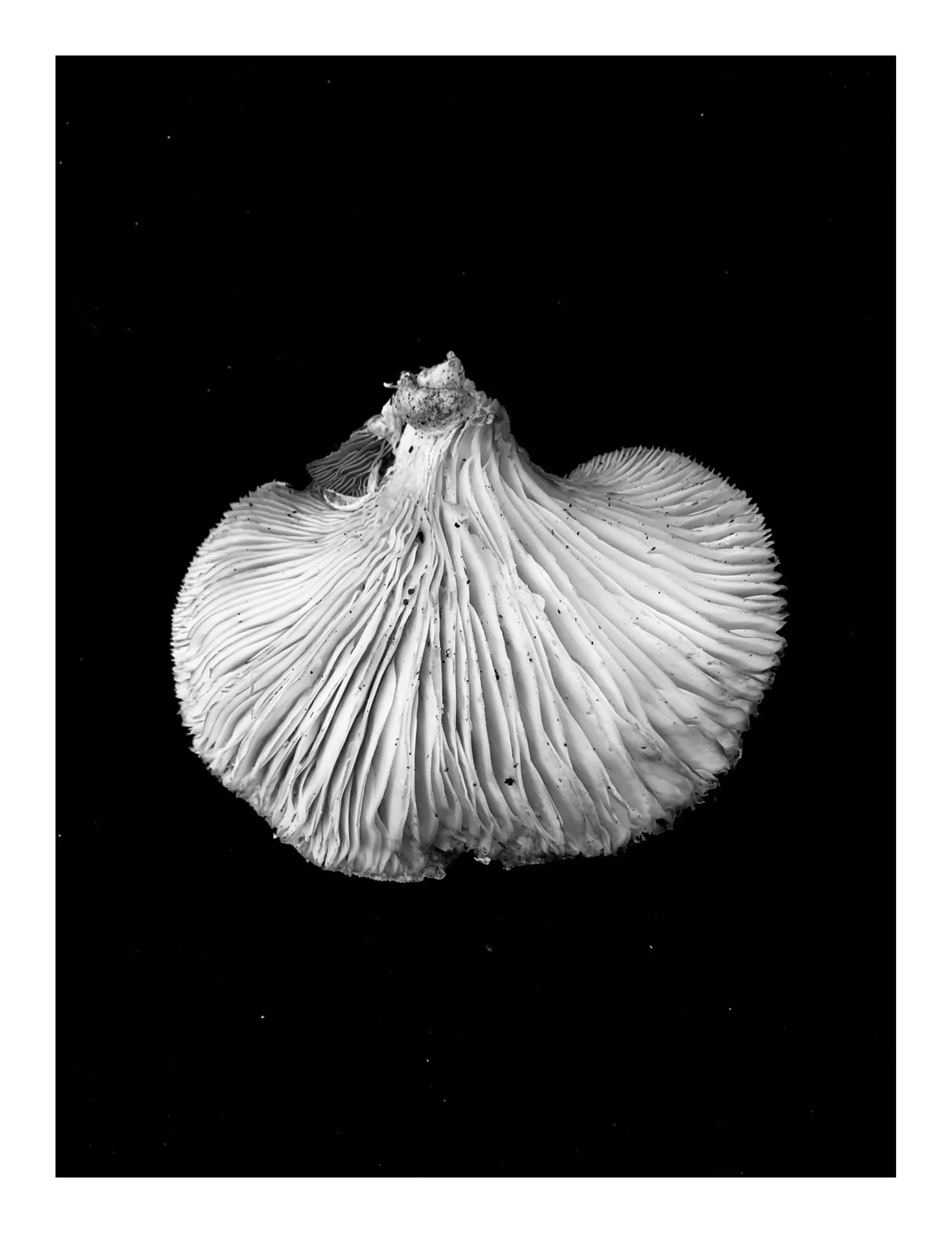

This winter the mushrooms locally caught my attention, and as I read about Entangled Lives by Sheldrake, Gathering Moss by Kimmerer and the History of Trees by Haskell, I was photographing a series of mushroom finds from walk with the dogs. Backed on velvet and lit by either natural light or an old clip-on spot from Ikea, I spent a lot of time playing with lighting and editing tools, immersed in the physical and literal lives of our brycologic and mycologic communities.

Mushroom Series 2020, Sulphur Cups, Limited Edition 125

Mushroom Series 2020, Bracket Funghi, Limited Edition 150

Rivers, Marigolds and Sadhus

In the winter I run a photography tour called Sacred Rivers, and in 2019 we explored the role of India’s River Ganges through the lens. The following portrait series of sadhus, their face painting and their marigolds, were taken in India in 2019, mostly at the Kumbh Mela.

Floating Votives, Sacred Rivers © 2019

Floating Votives.

These are marigold garlands, presented to the Hindu gods, following the spiritual flow of the River Ganges. I find myself observing the role of water in so many religious traditions. The Ganges River is a part of Hinduism’s creation myths, a critical natural resource valued in life and death, where life and religion are deeply intertwined. Rivers remain fundamental to life. A perfect channel to explore photographically.

The images find themselves into my personal portfolio here for a number of reasons. I am drawn to the sadhus use of ash to paint their bodies, sandalwood and vermillion on their foreheads as a spiritual marker, and marigolds to remind themselves of their karmic offerings.

Sadhus renounce worldly possessions and follow a spiritual path. This renunciation is reflected in their use of the resources around them, where sadhus use and imbue natural resources with spiritual meaning and consequence. Markings that run across the forehead are connected to Shiva, the markings referred to as Tripundra. Markings that run vertically are called Tilakas, worn by followers of Vishnu. Sandalwood mixed up with clay and vermillion to make a paste for these tilakas.

The baba below wears his head garland of fresh marigolds, honouring his god through their colour and offering. On his forehead is a simple tilaka running north to south, a sandalwood paste marking his religious tradition. The sandalwood trees are often logged illegally to make furniture and religious icons, the demand for the wood outstripping supply, and the sandal tree now ‘near vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List. How, then, will the sadhus find the raw materials for their paste?

Marigold Man, Kubh Mela, Sacred Rivers © 2019

The vermillion tilaki can just be seen on the forehead of this bearded pilgrim below. He had the most extraordinary face. He tied his headwear with very fluent, stylish flair, and in the corner is the ragged end of a piece of fabric that I initially mistook for a live flower. Fabric replicating nature. He was waiting for his spiritual baba to lead the procession to bathe in the River Ganges.

Waiting for Salvation. Sacred Rivers © 2019

This image below was taken in amongst the dust and smoke of the Kumbh Mela in 2019. His face was painted entirely in wood ash, thickly caked, mask-like, and the baba had chosen to wind lengths of marigolds round his Jata (dreadlocks). The use of wood ash represents the Sadhu’s death to their worldly life, the ash taken from sacred fires. At its simplest, burnt wood connecting energies. The Indian Government has recently banned extinguished cremations at Varanasi entering the Ganges in an attempt to protect water quality. This has been difficult for devout Hindus to come to terms with.

Smoke, flowers and ashes, Sacred Rivers © 2019

Mahuti Baba

Mahuti, the baba in the image below, has a simple wood-ash tripura on his forehead. At Varanasi, on the banks of the River Ganges, he follows Shiva in his ritual and practice.

What is interesting to me is the mask presented to the outside world, a spiritual, cultural or religious meaning attached, and the way in which the Sadhus make use of natural resources available to them.

Mahuti baba is wearing a large necklace of Rudraksha males under his beard, just visible in this image.

These are prayer beads made from the seeds of the Rudraksha tree, only found in the Himalayas, increasingly rare and sacred to followers of Shiva. Every sadhu has a Rudraksha, making use of the natural resources available. As the seeds become increasingly hard to find, plastic copies are used instead.

Mahuti Baba, Varanasi, Sacred Rivers © 2019

These images explore the intersections along an axis of photography and geography, where humans use their environmental resources to express themselves culturally and artistically.

I have been interested in the idea of mimicry and the role of costume in portraiture, particularly in relation to natural resources, for a long time. This started with masks and tribal bodymarkings, and reaches geographically across Europe and into Africa, where I grew up. Mirella Ricciardi’s work on recording the vanishing cultural practices in tribal Africa has been on my radar since I was a late teenager. Moving in a slow trajectory towards my own curation of these ideas, I have been working on images with the use of clay face masks in a series on anonymity, youth and ageing. Influences include Transfigurations by Lendhorff and Trulzch, and more recently the collaborators Hjorth and Ikonen, using Nordic folklaw and natural resources to develop their imagery. This plays into my interest with local folklaw practices and costume. Freger’s work on zoomorphism and costume connected with old customs of transhumance is of huge interest. The sadhu series opens a dialogue about how natural resources have become embedded in ritual and costume, raising wider questions about environmental sustainability.

Pinterest boards include visual references on second skin, masks and folklaw.